Set in Glenville, Ohio (a neighborhood on the East Side of Cleveland), the Karamu production of The Breakfast at the Bookstore, written by Lisa Langford and directed by Nina Domingue sheds light on a young woman, Dot, who wants to support the cause of the Black liberation movement by opening a bookstore. Despite the discouragement that her partner/common-law husband, who is a former Black nationalist is her common-law husband, gives her, Dot continues to prepare to open the bookstore with a free breakfast as its opening event.

For Dot, offering a free breakfast is more important than opening a well-stocked bookstore. The store still has no shelves for all the books she ordered and received.

The year of 1973 is 5 years after the 1968 uprising, a gun battle between the Cleveland police and an armed black militant group called the “Black Nationalists of New Libya, led by Fred “Ahmed” Evans (https://case.edu/ech/articles/g/glenville-shootout). Three policemen were shot dead, and scores were injured. Three nationalists and one bystander were killed. There are many versions of what happened, how it happened, and why it happened.

Dot (Kechanté), her much older common-law husband Sharpe (Prophet Seay), and their neighbor Haywood (Dar’Jon Bentley) live in the aftermath period of the shootout that had left people with anger, resentment, disappointment, and yearning for change. While Sharpe has “graduated” from the revolutionary period and took baptism of “Afrofuturism,” Dot clings to her excitement about the Black nationalist movement in her teens. Kechanté who took over the role of Dot after February 1, performed a young wanna-be revolutionary on the night I attended.

Prophet Seay played a middle-aged, disillusioned, former Black nationalist. Langford’s script calls for this character to go back to the 1960s; Seay compellingly portrayed a younger version of Shape who goes through different stages of realization and disillusionment. Dar’Jon Benley’s Haywood, a hired helper of Sharpe, is a young man who is caught in systematic brutality in the Italian neighborhood. Carolyn Demanelis’s Fran complements the show by portraying a closeted white mail carrier who is enamored by Dot and then psychologically and physically traumatized by her extraterrestrial experience without ever finding out what it is.

Scenic designer Laura Carlson-Tarantowski created a front room of their first-floor apartment of Sharpe, which Sharpe uses as an electronic repair shop, and Dot tries to convert it into a bookstore. The three pictures—a colorful Black Jesus, Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael—added a historical context to this interior landscape. At the same time, a total lack of women activists’ photos spoke volumes about Sharpe’s sexism and blindness—as Angela Davis stated in her foreword to the book Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party written by Stephen Shames and Ericka Huggins, 66% of the membership of the Black Panthers was female.

Through the three panel-store-front-windows, the audience can see the neighborhood stores across the street. On the outer frame of the arch, many historical photographs are projected (by T. Paul Lowry, digital media designer), including a voting rights march and the inauguration of Obama. This “history at a glance” dramaturgy reminds me of the first scene of George C. Wolfe’s The Colored Museum.

Suwatana Rockland’s costumes underscore each character’s history, age, and personality. Rockland also accentuates the shift between Act I and II by drastically changing the shapes, draping, and colors of Dot’s costumes. While the colors of Dot’s costumes are black and brown (and a red beret) in Act I, her brighter top with flare sleeves shows that the character is well into the 1970s, leaving her original fascination with the Black nationalist movement.

Jeremy Paul‘s lighting in red and deep-purple colors generates the extra-terrestrial atmosphere in resonance with Afrofuturism.

Sound designer Richard B. Ingraham prepared many pieces from the 1960s and 70s. Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Will Not Be Televised” is ironically and contrarily what eventually happened—the contemporary revolution “Black Lives Matter” happened as widely televised on social media.

Longford uses Afrofuturism (UFO traditions) as a thread to tie 12 scenes together. Afrocentrism is related to Black supernatural traditions in which ancestors’ spirits and stories guide their descendants to take them to the right paths. As in the Director’s note states, Afrofuturism was born in the art world as represented by Henry Dumas (1934-68), Sun Ra (1914-93, American Composer), and Funkadelic (a rock band formed in 1968). The National Museum of African American History and Culture defines Afrofuturism as ism that “expresses notions of Black identity, agency and freedom through art, creative works, and activism that envision liberated futures for Black life.”

In Langford’s play, Afrofuturism is presented through different characters. For example, the character of Sharpe had metaphorically visited outer space, where he learned all of the efforts to change white-centered systems are meaningless.

Though The Breakfast at the Bookstore is packed with so many ideas—feminism, transgenderism, Black nationalism, Afrofuturism, and today’s activism, what comes back at the end of the show is “Free Breakfast.” A free breakfast program was started by the Black nationalist party in the late 1960s to nourish children—both their bodies and souls. The “bookstore” was the venue that the Black activists used to educate and solidify their followers. Many Black-owned bookstore owners became the targets of the police and FBI harassment.

At the end of the show Sharpe “shows” Dot an invisible series of images. Dot’s reaction can be read as a surprise, disappointment, or shock. These unprojected images could be about recurrent violence and killings against Blacks by the police, as happens to Haywood in the play. Sharpe—a disillusioned, irrelevant former activist—may be unable to show positive images.

Lisa Langford is a Cleveland-based playwright. I enjoyed attending her Rastus and Hattie (Joyce Award-winning play) at the Cleveland Public Theater in 2019. She is a playwright who examines trauma and scars that African Americans have carried from the past, and The Breakfast at the Bookstore invites the audience to revisit the past of African Americans in Cleveland. And from the past, Langford invites her readers and audiences to the future with a new generation character, Dot, who is non-binary without a fixed ideology.

Since many of her audience members were not born in the later 1960s, some dramaturgical packet (performance guide) might have prepared the audience. Langford may want to include some explanation in the text in a way that the audience can quickly grasp what happened in the Shoot Out and what that impact was on the community. The same thing can be said about

Many of the transitions between each of the short scenes (seven in Act I and five in Act II) could be much faster. I would use area-specific lighting rather than realistic prop/scene changes for each transition. The Jelliffe Theatre is a conventional proscenium theatre. This play may be better presented in a Blackbox theatre or a thrust stage because those forms would invite the audience to the characters’ extraterrestrial experience.

As Domingue writes in her Director’s Note, Dot represents “the next generation of freedom fighters who refuse to be restricted by binaries.” Dot, as a transformative, non-binary figure, symbolizes the current movement (for the characters in the play, the future), which is more inclusive and intersectional. In fact, two of the founding members of the BLM movement, Patrisse Cullors and Alicia Garza, are members of the communities excluded from previous movements. What the characters see as their future (this part is left to the audience’s imagination) might be filled with female-identified community-based, local, state, and national activists and politicians from whom we have and benefit.

My friend who came to the show with me on February 3, 2024 told me that the character of Dot evokes both historical and contemporary female figures who dedicated (and are dedicating) their lives to change the system to help those who are underprivileged and to bring social justice. Some of the figures she listed include Fanny Lou Hamer, Angela Davis, Elaine Brown, Katheleen Clever, and Cori Bush. I would add Stacey Abrams. We all look forward to “meeting with” them as characters of plays that contemporary playwrights will craft in the future.

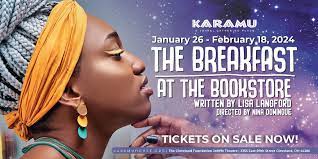

JANUARY 26 – FEBRUARY 18, 2024 | The Cleveland Foundation Jelliffe Theatre